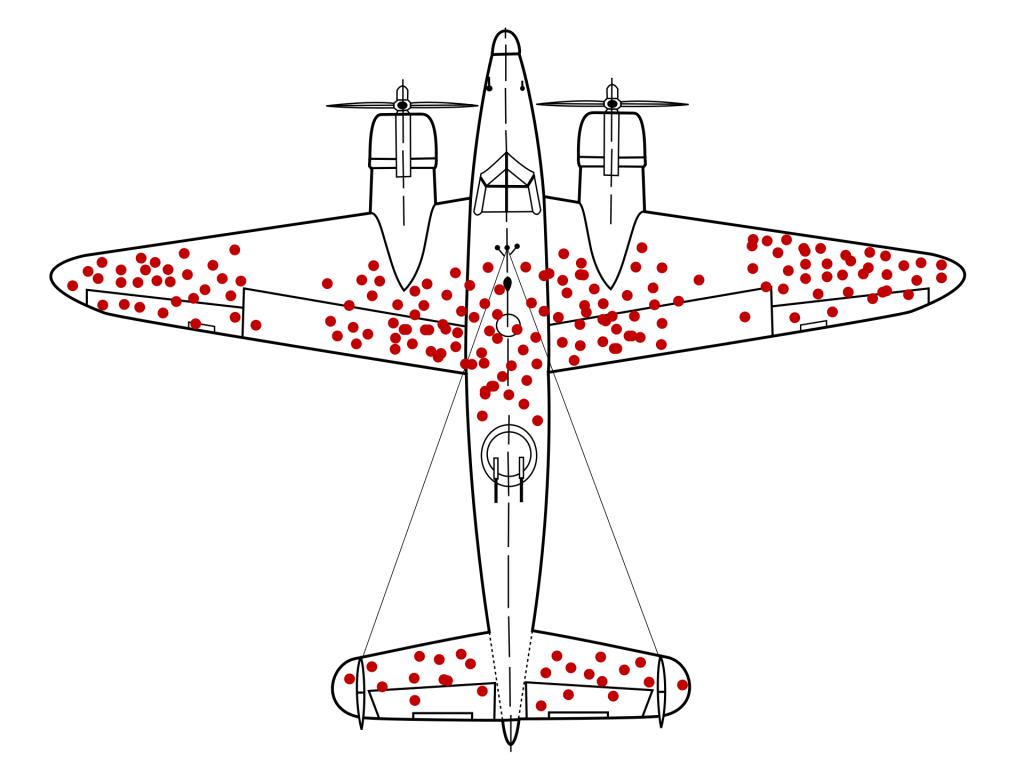

By Martin Grandjean (vector), McGeddon (picture), Cameron Moll (concept) – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102017718

In 1943, the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University conducted research on behalf of the US military regarding the damage that their aircraft were sustaining on missions. Military officials presented the group with analysis of where bullet-holes were showing up on returning planes. As you can see from the diagram above (which, as this article explains, isn’t much like what they drew up), these planes had lots of damage in areas like the wings, the fuselage and the tail. Intuitively, then, some officials sought to apply reinforcement to those parts of the aircraft. But Abraham Wald, a mathematician who had fled the Nazis in the mid-1930s, argued successfully that the additional armouring should be going on the spots where no damage was showing up, most prominently the engines. The reason for this was simple: in order for the planes to be included in the survey, they first had to return from battle. This story illustrates the idea of survivorship bias: when we analyse our decisions, we are apt to overlook entities that did not get through an implicit or explicit selection process.

If I had the attention of every senior leader, policymaker and education commentator for five minutes, I would teach them about survivorship bias. I think that understanding the principle is key to supporting the most disadvantaged, recruiting and retaining teachers, and using education to drive social mobility. In this blog, I want to prod around at the edges of the story of Abraham Wald’s planes to explore a few ways in which educational decision-makers would benefit from an awareness of survivorship bias.

1. Ghost planes: what does ‘survivorship’ even mean?

Aerial warfare in WW2 was characterised by huge casualties. Most strikingly, though, the unique nature of airborne combat means that those losses took place way out of sight, deep behind enemy lines. It’s this that generated the main problem that Wald faced when analysing damage on returning planes: it was impossible to break down the total number of lost planes into sub-categories based on what had caused them not to return. Although Wald’s suggestion that under-armoured engines were the most likely source of fatal vulnerability explained many losses, there would have been other causes of lost planes too: mechanical failure, human error and navigation problems will all presumably have prevented some planes from returning. But we can’t be sure how many. For want of better information, we lump all these lost planes together. Let’s call them ‘ghost planes’.

Ghost planes no longer exist to nearly the same extent. Technological advances mean that losing a plane for unexplained reasons is incredibly rare (although famously not impossible): it is in everyone’s interests to make causing a plane to disappear far more trouble than it’s worth. The same could be true in education, but for the time being, it isn’t. To take one example, media is awash with detailed stories of students getting into top universities – increasingly seen as the defining outcome of a successful school career – but at the other end of the scale, the ‘forgotten third‘ of students not passing GCSE English and Maths are treated as a homogenous lump of underachievers, like ghost-plane students (I wrote about this here).

These ghost-plane students don’t just disappear, though. Rather than bewailing their poor outcomes when these students show up in sources such as the Labour Force Survey and the Census, we could do much more to leverage the existing relationships that schools have with ghost-plane students. For example, many schools do ‘certificate awards evenings’ in the autumn term, in which the summer exam cohorts return for a celebration of their achievements. If schools used these evenings as opportunities to reach out to all students, and gathered curricular and pastoral feedback particularly from students who had not passed their exams, then not only would this allow them to target interventions more effectively for the upcoming cohort, it might also help staff to chase up potential NEET students, as well as allowing students who hadn’t made the grade to reclaim a sense of ownership and purpose over their schooling. In short, then, the existence of ghost-plane students is a policy choice, and one that could be mitigated against with quite small changes.

2. Heavy weather: the fallacy of ceteris paribus

Wald’s mandate was pretty limited. The design of the study focused on a single cause of aircraft failure – enemy fire – and sought an intervention that was likely, but still not guaranteed, to reduce losses. As a story about observable variables and probability, it’s as interesting for what it doesn’t tell us as what it does. As we saw above, it conveniently elides other potential explanatory variables. One particularly interesting one for our purposes is the weather.

Bad weather can be catastrophic for aircraft, and this was no exception during the war. Airforce commanders had to be strategic about the sort of missions they pursued at different times of the year. In much the same way, the school system is strategic about the ‘missions’ it chooses for children at different stages of their development, increasing in difficulty as they get older. To stretch the image in one dimension, we can think of standardised tests like GCSEs as a tried-and-tested training exam that every cohort of trainee bomber pilots does, in which they’re scored on various competencies (and, for our purposes, there’s live enemy fire – stay with me here). In an ideal world, every cohort would undergo this test at the same stage of their training, under similar atmospheric conditions. Although it’s not perfect, such a test provides a least-bad way to evaluate their abilities against a stable set of parameters and to gauge the effectiveness of the training you’re providing.

But what we’re seeing is that the metaphorical weather is getting worse with every passing year. The assumption of ceteris paribus – other things being equal – is what allowed Wald to state within the parameters of his investigation that adding more armour to planes’ engines was probably going to reduce losses. If he was providing that advice while staring out into an oncoming snowstorm, then it would have been taken much less seriously. In a sense, the money that the DfE has funnelled into curriculum and teacher qualifications in the current climate is the equivalent of the military buying loads of armour just as a vicious winter sets in. It’s a sunk cost, and it crowds out strategies that could make participants resilient to the challenges of the broader climate. This results in more lost planes, and demoralised staff as we persist with the fallacy that test conditions are stable from year to year.1 This then becomes cyclical: if we blindly insist that planes getting shot down are all we’re interested in, experts in the system will get frustrated and leave in droves, and we start to struggle with strategies for both the missions we assign and the wider climate2. We need to be mindful of the wider context when we compare from one cohort to another, and avoid being blinded by accountability that assumes parity across years.

3. Returning heroes and also-rans

Among the planes that Wald’s team inspected, some will have attracted more attention than others. Those with most bullet holes are likely to have been involved in more perilous encounters, and their pilots are more likely to have been garlanded with awards for gallantry and the like. The media seizes on stories of triumph over adversity, and these daring, brilliant pilots are held up as heroic role models for their decisive action and quick thinking.

Even though their risk-taking and brushes with disaster make bomber pilots terrible role models for state school students, narratives of unlikely triumph over adversity continue to dominate the educational airwaves. Every few months, a new feel-good story emerges about a down-on-his-luck boy getting a scholarship to Eton against all odds. Likewise, there are plenty of well-intentioned social media accounts with considerable followings shining a light on students who have reached dizzy academic heights despite huge challenges. These voices are an important part of ongoing work to diversify access to university in particular, but survivorship bias means that we are utterly blind to those who have worked just as hard, but who have not been quite so lucky3.

This was a massive problem when I was working on university applications strategy last year: students with ordinary grades would brandish these stories as evidence of the possibility that they could theoretically get in for Medicine or go to Oxbridge, impinging upon the already scarce time that my team had to support much more plausible candidates from disadvantaged households with their applications. Moreover, the more challenging the wider conditions are for students, the more the media seizes on particularly impressive anecdotal cases, and the easier schools with established reputations for bucking socioeconomic trends find it to continue their momentum (although this is not always achieved very ethically).

The depressing thing about all of this is that an education system producing a few heroic bomber pilots while sustaining ever greater losses is clearly not doing its job properly. To take a counter-example, Estonia’s education success often flies under the radar, but one striking aspect of their approach is a truly comprehensive approach, in which classes are mixed-ability and materials and school lunches are universally free. To go back to the analogy, they aren’t clamouring for heroic pilots – they’re building a force, and they’re losing far fewer planes along the way. Nick Hillman has written about the need for a better-articulated argument in favour of comprehensive education; this need has surely only grown more acute as conditions have worsened across the last few years.

So what?

The very nature of survivorship bias means that its lessons are easy to overlook. Here are a few that I’ve covered in this blog.

- Some of the most useful insights for schools are going to come from students who would otherwise slip through the cracks. Capturing their feedback is easier than we think and could be transformative.

- We aren’t comparing like for like when we look across different years facing the same exams. Awareness of changing climates (and efforts to ensure that students are as insulated as possible from those changes) can make interventions much more effective.

- The media chase outliers, and some students lean into underdog status. If you’re courting media attention as a school, it’s unlikely that your practices are setting a replicable example for other schools and settings.

In the next couple of weeks, I hope to write a few pieces springing from some of the ideas I’ve raised in this first outing. Let me know your thoughts.

Notes

1. It’s possible to critique this by arguing that norm-referencing is an effective form of mitigation against cohort instability amid changing wider conditions. This is largely true, but it’s worth remembering two things. First, as anyone who’s taught undergrads lately will tell you, not all A-grades are created equal: the signalling power of one grade masks a wide range of different abilities, particularly in the wake of the Covid grading scandals. Second, it doesn’t account for the composition of the cohort. If the broader climate is challenging, then we’re much more likely to see only the strongest candidates surviving (analogous to the most expensively-constructed planes returning from missions). This is clearly undesirable.

2. I am finalising this on the morning of 15 December, and Education Policy Institute have just published a report alluding to exactly this phenomenon in light of the pandemic. It will be interesting to see whether the DfE is willing to work with other departments (notably the Treasury) in a bid to find a joined-up solution to the disadvantage gap.

3. When I was a teenager, the prospectus of my school’s sister school bore this deathless quote from a student: “When I tell people I go to [posh girls’ day school], they say ‘Gosh! You must be really clever.’ I tell them, ‘No – I’m just really lucky.’” Priceless.

Leave a comment